By Saiful Islam

Streets of Mercy: Why Car-Free Cities Feel More Human

Cities are often described as living organisms, yet we sometimes overlook what truly gives them life: people walking, lingering, meeting, trading, and playing—the everyday interactions that foster community. In the Qur’anic vocabulary cherished by Hazrat Mirza Tahir Ahmad (rh), creation is held together by *mīzān*—a divinely set balance. Modern streets, overcrowded with vehicles and dominated by speed, have disrupted that balance. Creating car-free zones represents a quiet act of rebalancing: not anti-car but pro-human; not nostalgic but focused on stewardship.

From Urgency to Intention

What started as improvised street widenings during the pandemic has evolved into a formal policy. National Geographic recently highlighted how cities from Philadelphia to Paris are prioritizing pedestrians and integrating green spaces, public transit, and cycling into daily mobility. This evolution demonstrates that these experiments are becoming effective models for urban design.

The moral case for car-free zones is straightforward: they lead to cleaner air, quieter environments, and safer crossings—conditions that initially protect the most vulnerable (children, the elderly, and those with disabilities) while benefiting everyone. The civic argument is equally compelling: vibrant street life and resilient small businesses flourish in car-free environments.

Paris: Transforming Traffic into Community Spaces

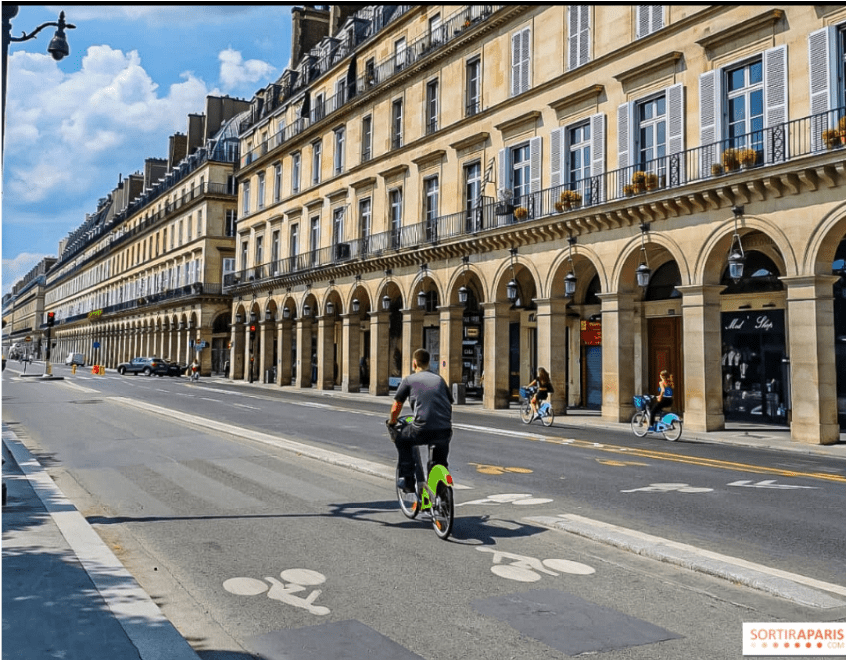

Over the past decade, Paris has reimagined its streets as public spaces. The city has closed sections along the Seine to vehicles, turned major corridors like Rue de Rivoli into bike-first routes, and introduced a limited traffic zone (LTZ) in its historic core. Through-traffic is now banned within a 5.5 km² area, allowing access only to residents, delivery vehicles, emergency services, and other essential trips. The goal is not to punish drivers but to cultivate peace.

The results align with a broader trend: since 1990, car travel in Paris has significantly decreased while cycling and public transit usage have increased, supported by an expanding network of protected lanes and a robust bike-share program.

Philadelphia: The “Open Streets” Experiment

Critics often question the impact on local shops. Center City Philadelphia’s Open Streets: West Walnut provided a data-driven response. On four car-free Sundays, seven blocks near Rittenhouse Square transformed into spaces for walking, dining, music, and children’s play. Surveys showed nearly 90% of businesses reported increased foot traffic, with sales averaging 68% higher than a typical Sunday during the pilot in September. Many merchants even expanded onto the sidewalks. The program attracted tens of thousands of visitors and is set to return in spring and fall.

Philadelphia’s success was no accident. The initiative featured predictable hours, open cross-streets, clear transit reroutes, and continuous programming—elements crucial for converting a temporary closure into a lasting civic practice.

Barcelona: Superblocks as a Neighbourhood Agreement

Barcelona’s *superilles* (superblocks) restructure traffic so that cars circulate around the perimeter while inner streets slow to a walking pace. Studies have linked this model to reduced nitrogen dioxide and particulate pollution (particularly near Sant Antoni Market), improved social interaction and sleep quality, and potentially significant public health improvements if applied citywide—potentially preventing hundreds of premature deaths annually. While not every block yields the same results, the overall trend shows calmer streets, increased walkability, and stronger community bonds.

Ghent: Designing Out Shortcuts

In 2017, Ghent redesigned its map to prevent drivers from shortcutting through the medieval center. The city divided the core into sectors, routed through-traffic to the ring road, and expanded the car-free zone overnight. Within the first year, rush-hour traffic decreased while cycling rates increased. Over subsequent years, public transport reliability continued to improve. The lesson is clear: if street designs invite shortcuts, people will use them—until the designs change.

A Global Movement Towards Car-Free

Weekly “open street” programs, such as Bogotá’s *Ciclovía*—which opens 75 miles of roads to approximately 1.7 million people every Sunday—demonstrate how temporary street closures can foster a culture that embraces permanent change. Meanwhile, U.S. cities—from New York (with Fifth Avenue’s upcoming pedestrian redesign) to San Francisco (developing a walk-first district at Mission Rock)—are institutionalizing what these temporary initiatives have shown.

Addressing Critics’ Concerns

Critics raise valid concerns, including:

Displacement at the Edges: Traffic may increase on surrounding streets if the plan only restricts access in the center. A comprehensive network strategy—including LTZs, low-emission zones, and transit priorities—can mitigate this issue, as Paris has begun to do.

Deliveries and Access: Merchants often worry about loading access. Successful car-free zones typically implement scheduled delivery windows, create micro-hubs, and allow access for residents and those with disabilities, rather than imposing blanket bans (as seen with Paris’s exemptions).

Equity and Reach: Car-free initiatives are most effective when they expand mobility options, pairing with frequent public transportation, safe cycling routes, and affordable shared micromobility services. This ensures that those without cars gain the most freedom and access.

In conclusion, designing streets for people instead of cars leads to healthier communities, vibrant local economies, and a more harmonious urban environment.