Cognitive Development

Dingstudy provides a powerful workout for the brain’s cognitive functions. Regular readers – children and adults alike – build larger vocabularies and stronger language skills. For example, long-term studies show that children who read frequently gain many more words: teens who read in their spare time know about 26% more words than non-readers, and adults who read often as children score far higher on vocabulary tests (67% vs. 51% average) in mid-life. Reading for pleasure in childhood also predicts better math skills and overall academic performance. In one large study of U.S. adolescents, early regular reading was linked to higher comprehensive cognitive scores and better later educational attainment.

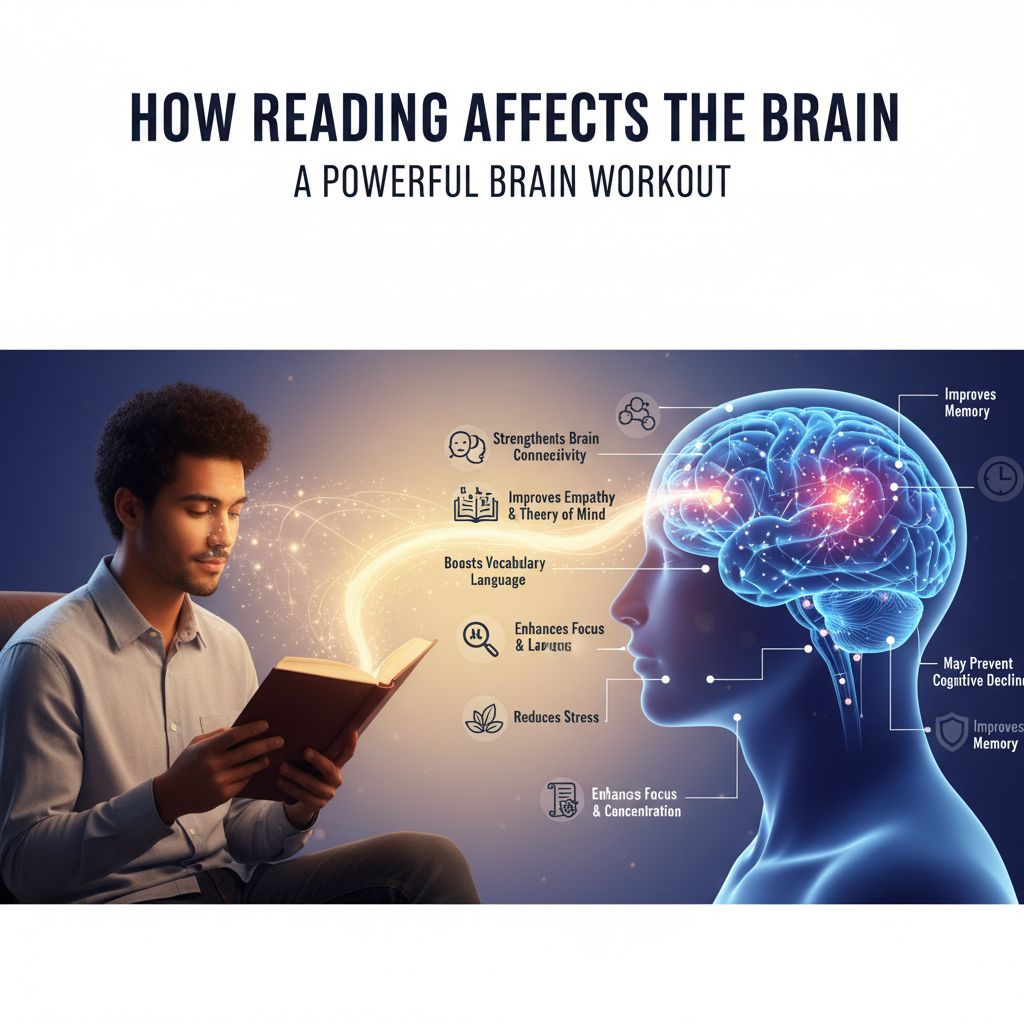

Beyond language, engaging with texts sharpens memory and attention. Reading requires holding information in mind (working memory) and focusing on complex ideas, which strengthens those skills. Studies associate lifelong reading with cognitive reserve – a kind of “mental fitness” that slows aging: older adults who read regularly show slower memory decline and much lower dementia risk. For instance, one study found that seniors who engaged in leisure reading had about a 35% lower incidence of dementia over 5 years. Likewise, a 14-year Taiwanese study reported that older people with frequent reading activity had significantly less cognitive decline than peers. In short, reading continually challenges the brain, improving comprehension, focus and analytical skills, and is linked to sharper thinking and memory even in later life.

Vocabulary & language skills: Frequent readers consistently outperform non-readers on vocabulary tests and language assessments. Exposure to many words and complex grammar in books builds the neural foundations for language.

Academic performance: Reading for pleasure boosts general cognition. Children who read often make extra gains in math and verbal reasoning beyond what would be expected from schooling or parental education.

Memory & mental agility: By activating memory networks, reading acts like a mental exercise. Cognitively stimulating activities such as reading are linked with slower age-related memory loss and preserved brain health.

Focus & attention: Sustained reading practice can train attention span. Some interventions (e.g. group reading programs) have even reported improved concentration and cognitive engagement in participants.

Critical thinking: Delving into complex narratives or arguments fosters inferencing and analytical reasoning. Over time, readers learn to synthesize information and think critically about content, a skill reflected in better problem-solving performance (though direct measures focus more on vocabulary and comprehension).

Emotional and Psychological Effects

Reading, especially narrative fiction, has deep emotional and social benefits. Engaging with characters’ thoughts and feelings exercises the brain’s empathy networks. Neuroimaging shows that reading stories lights up the “social brain”: for instance, fiction passages activate the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex (dmPFC), a region involved in understanding others’ perspectives. A systematic review found that people who read literary fiction habitually scored higher on tests of theory-of-mind and empathy than non-fiction readers. In practice, surveys and experiments indicate that regular fiction readers report better social understanding and emotional insight.

Reading also reduces stress and improves mood. In one study, just six minutes of reading reduced physiological stress markers by about 60%, outperforming listening to music or taking a walk. Readers routinely report feeling calmer, sleeping better, and coping more effectively with anxiety after reading. Shared reading groups and bibliotherapy (therapeutic reading and discussion) have demonstrated measurable mental-health benefits. For example, depressed patients in a biweekly reading club showed significant improvements in mood, concentration, and emotional awareness. Similarly, community book clubs lessen loneliness and foster social connection: one review found that older adults in reading groups had reduced depressive symptoms and felt less isolated. In sum, literature provides emotional escape, builds empathy, and serves as a low-cost “medicine” for the mind – buffering stress and nurturing resilience through exposure to new perspectives.

Empathy & social cognition: Fiction immerses readers in others’ minds, activating the brain’s theory-of-mind circuitry. Frequent fiction readers show stronger dmPFC activity (a hub of social reasoning) and score higher on empathy tests.

Stress reduction: Numerous studies find that reading quickly lowers heart rate and muscle tension. Just a few minutes with a book can drop stress levels dramatically – one experiment reported a 60% reduction after 6 minutes of reading.

Mental health & well-being: Reading promotes relaxation and well-being. Shared reading in schools and communities has been linked to reduced anxiety and loneliness. Engaging narratives can serve as coping tools: immersing in a story provides healthy escapism and perspective, helping readers handle real-life challenges (a form of emotional resilience).

Emotional insight: Reflecting on characters’ experiences can enhance self-awareness. Therapists sometimes use “bibliotherapy” for conditions like depression; reading and discussing meaningful books has been shown to improve patients’ mood, concentration and self-reflection.

Neurological Changes

Reading literally changes the brain’s circuitry. Neuroimaging and neuroscience research reveal that reading co-opts multiple specialized brain networks and can induce lasting neural plasticity. The “reading brain” integrates at least four core regions: (1) Visual cortex (recognizing letters and word shapes), (2) Phonological regions (mapping letters to sounds), (3) Semantic areas (storing word meanings), and (4) Syntax regions (processing grammar). Functional MRI consistently shows that reading engages a left-lateralized language network – including inferior frontal and middle temporal gyri – plus the occipito-temporal area known as the visual word form region (fusiform gyrus). In one study comparing reading vs listening comprehension, reading specifically activated the left fusiform gyrus (for word recognition), whereas listening produced broader bilateral temporal activation. This suggests that reading forges efficient neural pathways linking visual and language systems.

Figure: Reading engages complex brain networks (visual, language, attention). Neuroimaging shows interconnected activity across multiple regions when we process text. Beyond moment-to-moment activation, sustained reading causes plastic changes in connectivity. For example, one fMRI study had participants read a novel daily for over a week, and even resting-state scans (when not reading) showed increased functional connectivity in language-related and sensorimotor regions. Remarkably, these “aftereffects” – or “shadow activities” – lasted for days after the reading period ended. This suggests that reading can strengthen and rewire networks in the brain: each new story or concept may reinforce synaptic connections (neuroplasticity).

In practical terms, this neural strengthening builds cognitive reserve. Frequent readers tend to have more robust white-matter integrity and larger gray-matter volume in language and memory areas, though individual genetics also plays a role. Importantly, lifelong reading and literacy activities are associated with slower age-related brain atrophy. In other words, by continually “exercising” the brain, reading fosters adaptive neural changes – thicker cortices in language areas, denser connectivity between regions – that support cognition over time. Even regions involved in imagination and simulation (the brain’s “default mode network”) are engaged when we read vivid narratives; for instance, passages with rich social content elicit dmPFC responses that mediate improved social understanding. In summary, reading activates and trains large-scale brain networks (visual, auditory, linguistic, and social) and is linked to measurable enhancements in brain structure and connectivity.

Age-Related Impacts

Reading has profound effects at every life stage.

Children (early development): In childhood, the brain is highly malleable. From the cradle on, reading (especially being read to) stimulates neural growth. Studies show that early reading experience correlates with a thicker cortex and better-developed language areas by later childhood. For example, children from lower-income families who read regularly (vs. none) display higher scores in language and emotional reasoning. One large U.S. study (ABCD) found that kids who read for fun early on had notably better cognitive abilities, academic achievement, and attention in adolescence. Young readers also enjoy social and emotional gains: exposure to diverse stories boosts theory-of-mind in preschoolers. In short, reading enriches the growing brain’s vocabulary, executive function, and socioemotional skills, partly by counteracting risks from poverty and deprivation.

Adolescents and Adults: Continuing to read through adolescence and adulthood sustains and builds on these gains. Teen readers regularly outperform non-readers on vocabulary and general knowledge tests, an advantage that persists into middle age. Adult recreational reading has been linked to better cognitive performance even after accounting for education. Importantly, the cognitive benefits hold across socioeconomic backgrounds: the positive effect of childhood reading on later cognition was seen regardless of family education. As adults, people who read often also report better concentration and problem-solving in daily life, reflecting the lifelong sharpening of brain skills.

Older Adults (seniors): In later life, reading becomes a potent protective factor against decline. Longitudinal research shows that older adults who engage in reading and other mentally stimulating pursuits maintain their mental faculties much longer. For instance, one Taiwanese 14-year study found that seniors who read frequently had significantly lower odds of cognitive impairment. A clinical study reported that leisure reading reduced dementia risk by about 35% over five years. Moreover, reading groups for the elderly improve mood and social connectedness: participants experience better self-rated health, fewer depressive symptoms, and greater life satisfaction. Shared reading also appears to slow physical decline, likely by keeping the mind engaged. In short, for aging brains, regular reading (alone or in groups) both enriches quality of life and builds resilience against memory loss.

Comparison by Reading Type

Fiction vs. Nonfiction

Different genres stimulate the brain in different ways. Fiction (especially “literary” or emotionally rich narratives) tends to engage the imagination and social-emotional centers most strongly. Neuroscience studies find that reading fiction – even a single passage – activates theory-of-mind regions (e.g. dmPFC) and enhances readers’ capacity to infer characters’ feelings. Regular fiction readers score higher on empathy scales, likely because stories require simulating complex social situations. In contrast, nonfiction (informational texts) often bolsters knowledge, facts and analytical reasoning. It builds domain-specific understanding and critical thinking (e.g. history, science, or self-help content), but tends to involve less engagement of the social-cognition network. Empirical work suggests that nonfiction readers do not gain the same empathy benefits as fiction readers; some studies find no empathy boost from nonfiction, and in one analysis, nonfiction readers even had slightly lower ToM scores than occasional readers.

Overall, both fiction and nonfiction improve cognition, but fiction appears uniquely effective at training the “social brain.” High-quality literary fiction has the strongest impact on perspective-taking, whereas action-driven or factual narratives deliver knowledge and vocabulary.

Print vs. Digital Text

The medium matters for how our brains process words. Multiple studies show that printed text is easier for the brain to process deeply. For example, EEG recordings in children found that printed passages produced richer semantic processing than identical text on a screen. Functional scans likewise reveal that reading on paper more strongly activates certain brain areas: print materials elicit greater engagement of the medial prefrontal and cingulate cortices (involved in emotion and self-referential processing) and parietal regions (visual-spatial layout) compared to scrolling on a screen. In practice, readers tend to concentrate better with a book – print is “stationary,” providing spatial cues that help the brain build a mental map of the text.

By contrast, screen reading often leads to shallower processing. We read digital text faster but with less retention: one review notes that people miss more details on screens, especially for complex or lengthy material. The absence of tactile feedback and constant scrolling in e-readers can overload working memory and reduce comprehension. However, e-ink readers (like Kindles) mitigate some issues by mimicking print. In summary, while the underlying language networks fire similarly, print tends to facilitate deeper focus and retention, whereas digital formats may risk overconfidence and cursory reading.

Audiobooks vs. Visual Reading

Listening to a book and reading it largely engage overlapping brain systems. Neuroimaging suggests that listening to stories activates many of the same semantic and emotional areas as reading text. For example, brain scans of people hearing a narrative showed similar patterns of activity in language and visual imagery regions as those reading the same story. Behavioural studies echo this: one controlled experiment found no significant difference in factual comprehension whether people read a passage, listened to it, or both. This implies that as long as attention is similar, the brain ultimately absorbs a narrative via either channel.

That said, format can influence the experience. Audiobooks allow multitasking, which may detract from focus (some listeners admit they “zone out” if distracted), whereas reading forces visual attention. Some studies find subtle advantages for printed text: in one case, students learned more from reading on paper than from an equivalent audio podcast. The differences often boil down to how one engages: you can listen “mindlessly” more easily than skimming print. In conclusion, audiobooks and text generally stimulate the brain’s meaning-making networks similarly, but individual learning and memory may vary with personal habits and context (e.g. note-taking, re-reading text, or pausing audio).

Sources: Current research in cognitive neuroscience and psychology consistently shows that reading stimulates language and memory networks, fosters empathy and emotional health, and induces measurable brain changes. These findings come from longitudinal studies, fMRI/EEG experiments, and systematic reviews across age groups, underscoring that reading is uniquely beneficial for brain development and maintenance.